New Tailwinds of the Latin American Credit Market

- Walter Pereira and Team WhiteSight

- 8 mins read

- Fintech Strategy, Partnerships

Table of Contents

As society developed, trust prevailed in the environment of personal and business life. Trust, in the financial world, is nothing more than credit. We trust in the future and then we trust in people and things. To give someone credit is to believe, at the very least, that the other person will pay you back. The financial world works in two ways: (i) the creditor’s position (pay now, live later) and (ii) the debtor’s position (live now, pay later).

In Yuval Harari’s book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, the author states that at a certain point in our history, credit gained a new model. Much more scalable and based on guarantees, we started financing large sailings in the Americas; family businesses; and, more recently, technology companies that directly impact our lives today.

The trust expressed by credit manifests itself in different ways and intensities around the world. It is common to see developing countries with less developed credit markets than developed countries. This is often due to the low level of access to financial services by the population for decades, as well as the development of financial systems in these countries.

However, a new opportunity for us to build a more mature and democratic credit market, especially in emerging countries, awaits us. Open Banking, fintechs, banks, and non-financial enterprises will be the protagonists of this new phase of credit in Latin America.

Basic Settings of the Financial System

A bank, in economic literature, accepts deposits and issues credit, and earns the interest differential between the two. These credit and transaction services enhance the well-being of the individuals who receive them. Thus, access to a nation’s financial services is linked to the level of economic and social development of a given country.

When we look at the financial history of countries with more mature financial systems (developed countries) and countries with more archaic financial systems (developing countries), we verify that the developed countries have focused heavily on meeting the banking and financial needs of consumers and businesses. Whereas, in the developing countries, credit was often controlled, reserved for priority projects and sectors. Outside these privileged sectors, credit was only available in informal markets at very high rates – resulting in a notable financial exclusion.

So, when we go back to the present day, we are able to understand some characteristics of the Latin American financial market. According to a16z, in Mexico more than 50% of Mexicans do not have a bank account; more than 30% do not have access to any financial product; and only 31% have access to credit services.

In Argentina, although the country has a law that requires all banks to offer a free bank account to anyone with a valid identity card, migrant workers and low-income Argentinian

citizens who do not have an identity card are excluded from the financial system. Data from 2018 show that 57% of low-income Argentines did not have a bank account. In Brazil, 16.7% of Brazilians still live in families without access to banking services. The less affluent regions from Brazil are the ones that suffer the most in relation to financial inclusion.

The New Tailwinds

Coronavoucher’s Impacts

With the advent of Coronavoucher in the region, Latin America has seen accelerated financial inclusion. According to a Mastercard study, as of August 5, 2020, 66 million people received the subsidy, and an estimated 36 million of them had no bank account before — about 17% of the Latin American population entered the financial system in a few months. With more agility and lower operating costs, neobanks and fintechs supported and enabled the Coronavoucher — or other social programs — to reach more families impacted by the pandemic.

In Brazil, the largest public bank, Caixa Econômica Federal (CEF), created an application that enabled beneficiaries to receive the Auxilio Emergencial, and digital wallets allowed beneficiaries to receive Merenda em Casa. In Colombia, the Ingreso Solidario was available through traditional banks and 3 digital wallets. In Argentina, the Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia was available through all private and public banks, but not digital wallets. It seems that this new phase is inclusive, democratic, and thriving.

According to the Mastercard report, the social benefit programs related to COVID-19 helped to financially integrate more than 40 million people in Brazil, Colombia, and Argentina alone. Brazil, for example, saw its unbanked population reduced by 73%, while Colombia and Argentina by 8% and 18%, respectively.

As more people are added to the financial system, they are able to obtain credit and other financial products and services. In the post-pandemic period, easier access to credit will be essential to overcome the financial difficulties intensified by the pandemic.

Open Banking Implementation

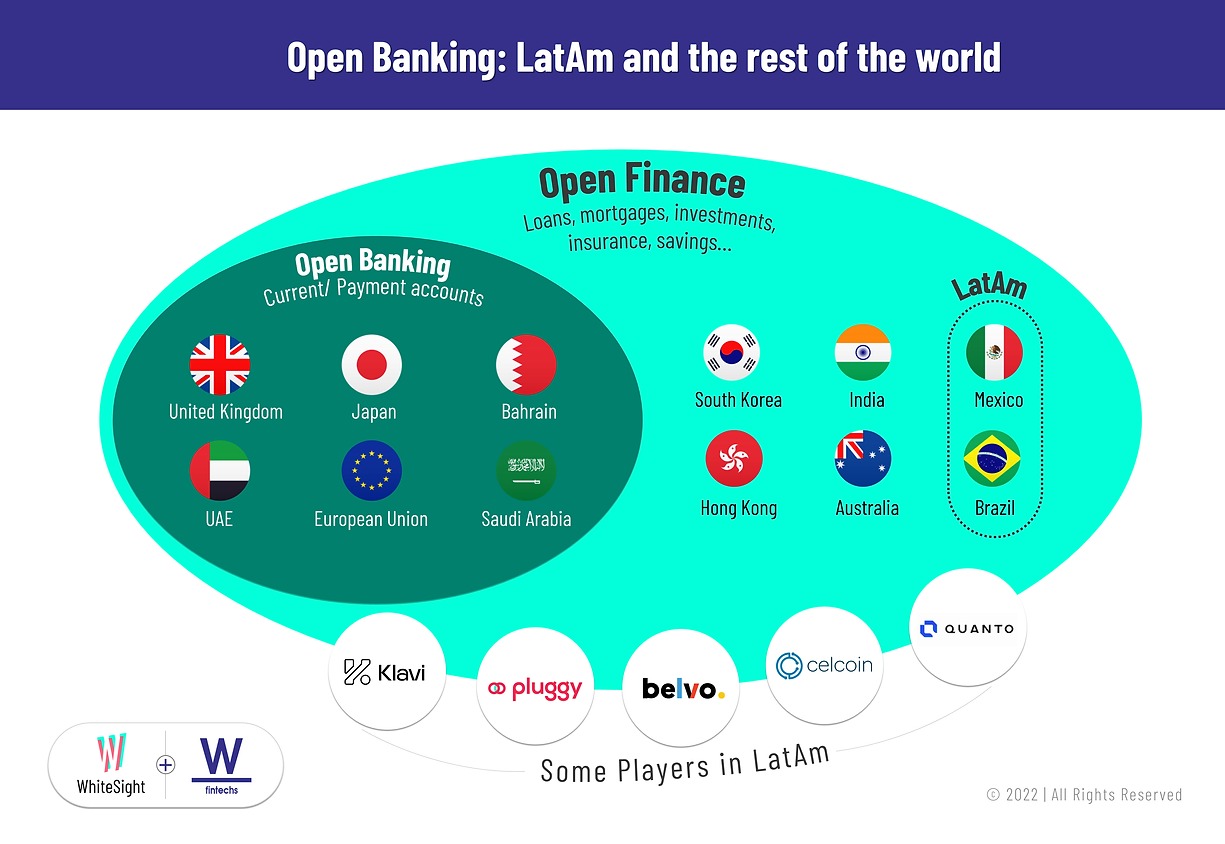

The current bet on the part of governments and private companies is credit. In Latin America, with an incipient credit market, new players (fintechs and neobanks, for example) have been betting on technology and favorable regulation to design a new scenario for the offering of credit. Following a global trend, countries in the region are developing Open Banking initiatives.

In short, Open Banking offers more options when choosing financial service providers, while making it easier for consumers to switch from one player to another. Around the world, Open Banking has been a driver of financial inclusion and democratization of financial information among players. However, in Latin America, it is expressed in different ways between countries in the region.

In Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, Open Banking is still in its early stages. In Argentina, for example, there is still no regulation or standardization of APIs, however, the BCRA (Central Bank of Argentina) has advanced a series of regulations that favor interoperability between institutions.

In Chile, at the end of 2020, the Financial Portability Law was approved, allowing individuals and companies to change their service providers freely.

In Uruguay, the Central Bank of Uruguay called upon policymakers, IT companies, fintechs, academics, and other interested parties to discuss Open Banking. But still, the country has not passed any law or regulation on Open Banking.

In Brazil and Mexico, discussions and regulations have been more advanced. Mexico was the first country to develop Open Banking regulations. In 2018, the Fintech Law was passed, which required around 2,300 financial entities to share their data. In Brazil, the Central Bank of Brazil started the fourth phase of Open Finance on December 15, 2021. Both countries, Mexico and Brazil, already refer to Open Banking as Open Finance, that is, the data will go beyond banking data — including data from insurance companies, investments, and others.

In Brazil, specifically, companies like Finansystech and Celcoin have shaken the partnership and regulatory market. Finansystech, for example, partnered with the Brazilian Stock Exchange, B3, to launch a platform that helps insurers adhere to Open Insurance. Finansystech’s proposal is to provide all the infrastructure for insurance companies to comply with the rules and facilitate the management and exchange of information between the parties.

Celcoin was authorized by the Central Bank of Brazil to operate as a Payment Institution (IP). With the license, Celcoin will be able to offer new infrastructure solutions in financial services.

These recent movements in the Brazilian market, for example, concern the region’s expectations of gains in financial inclusion and customer experience, as well as a maturing and democratization of the credit market.

Credit’s New Phase

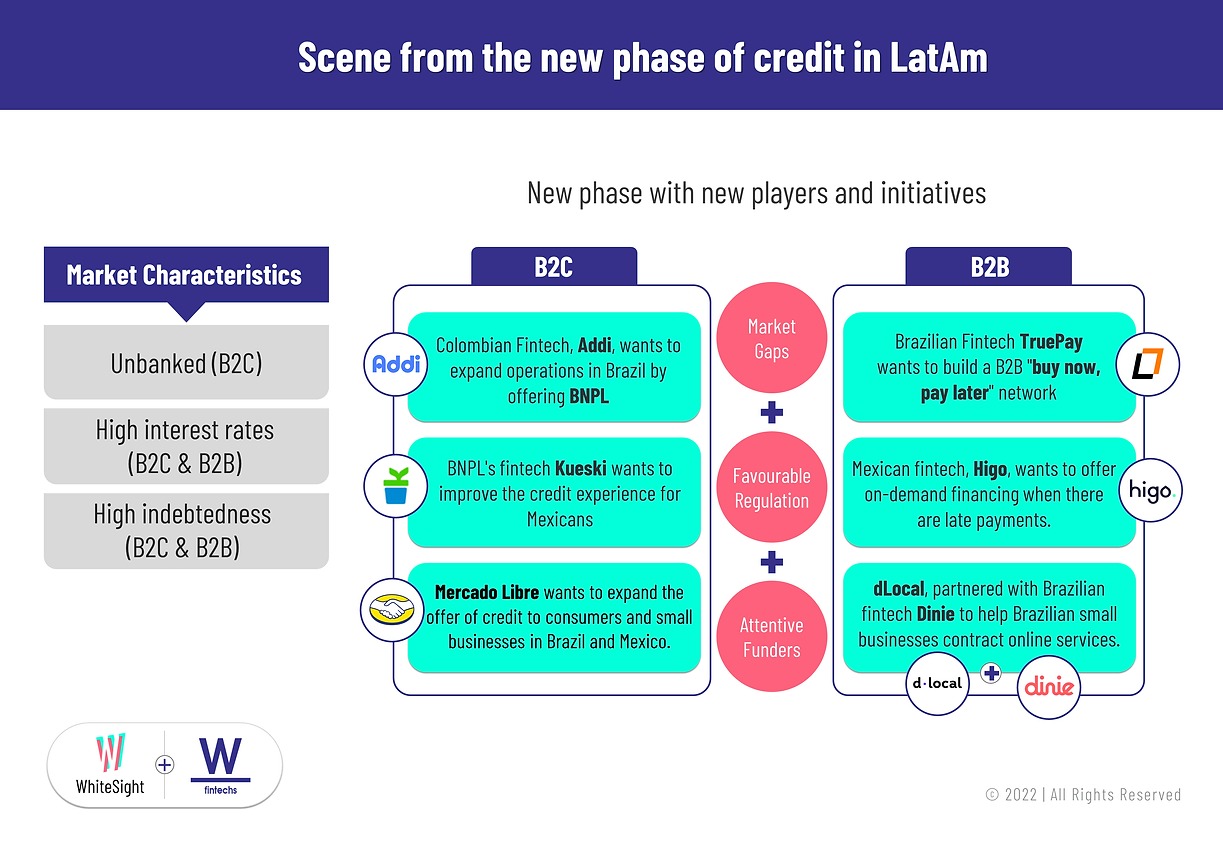

Favorable regulation has encouraged investors and entrepreneurs to create new players and mature existing businesses.

The Brazilian credit market still has many challenges. In 2019 alone, for example, credit card interest rates were close to 300%. Fintech Open Co, which emerged from a merger between Rebel and Geru is spearheading the objective of “finance consumption for Brazilians in a healthy way”. In December 2021, it raised USD 115 million in a round led by SoftBank.

Mercado Libre took out a USD 375 million financing line with CitiBank in November 2021. The proposal is to expand its credit offer to consumers, entrepreneurs, and small businesses in Brazil and Mexico. The company plans to allocate USD 225 million in its operation in Brazil and USD 150 million in Mexico.

In August 2021, Argentine fintech Ualá raised USD 350 million and was valued at approximately USD 2.5 billion. Fintech offers a complete financial ecosystem, offering bill payment, investment products, personal loans, BNPL, and insurance. The company, which aims to financially include the Latin American population, says 65% of its users had no credit history before downloading the app.

BNPL provider, Kueski, founded in Mexico, has secured $202 million in equity and debt funding. Its proposal is to improve the financial experience of Mexicans, in addition to maturing the local credit market. Kueski took advantage of the pandemic to grow its customer base and use the collected data to improve its machine learning and AI models.

In Brazil, players like TruePay are looking to take advantage of a market that for years was underserved by large financial institutions: Business to business (B2B) credit. In November 2021, the company received a contribution of USD 32 million. TruePay wants to build a B2B “buy now, pay later” network where sellers (industries) can extend credit without being exposed to default risk and where buyers (traders) access credit to buy stock from their suppliers in an integrated manner and for free.

In a model that addresses both credit and financial management, Mexican fintech, Higo, wants to change the reality of Mexican SMEs when it comes to B2B payments. Higo’s goal is to build a simple way for companies in Latin America to pay, collect and finance their invoices. The company also wants to offer on-demand financing when there are late payments.

In January 2021, Uruguay’s unicorn, dLocal, partnered with Brazilian fintech Dinie to help Brazilian small businesses contract online services. Together, the two fintechs will allow entrepreneurs to pay for services in installments without the need for a credit card — rare for companies of this size — or bank slip.

Regarding the BNPL for B2C, Brazilians already have previous experience with this concept. Known as “crediário” and present since the 1950s, the new BNPL model offers a digitalized and smarter experience of something that is already old among Brazilians.

VirtusPay, for example, raised BRL 125 million in debentures to further strengthen its BNPL solution in Brazil. banQI, the digital bank of Casas Bahia — one of the largest retailers in Brazil and the first store to offer installment purchases in the 1950s — has also used technology to improve its risk models and offer credit to its customers.

In addition to the private sector, the Central Bank, through Pix, has been innovating both in the payment market and in the credit market. The arrival of Pix Agendado, which combined with the BNPL models, will cause a direct impact on how consumers pay and companies receive.

Where These Winds Will Take Us

Latin America is experiencing a moment of transformation — with tailwinds from investors, entrepreneurs, and regulators. The region, which at the beginning of the century saw a reduction in inequality and poverty, is currently experiencing a period of change in the formation of its financial system.

With problems still related to access to credit and financial exclusion, Latin America is betting on initiatives such as Open Banking to expand access to financial services, as well as reduce their acquisition costs.The growth in the number of fintechs in Brazil and Mexico, for example, represents the market failures that these countries still face, while representing great opportunities for entrepreneurs to solve.

Credit is a fundamental tool for the progress of nations. It is through credit that people and companies are able to finance their plans. Latin America is writing a new chapter in its financial history, and it seems that this new phase is inclusive, democratic, and thriving.

Authors

Walter Pereira

Consultant, Angel Investor, Speaker and Publisher at W Fintechs

Curious minds uncovering valuable insights, united by their love for fintech.

| hello@whitesight.net

Curious minds uncovering valuable insights, united by their love for fintech.

Already a subscriber? Log in to Access

Unlock this blog

Gain exclusive access to this blog alone.

Radar Subscription

Select a membership plan that resonates with your

goals and aspirations.

Not Ready to Subscribe?

Experience a taste of our expert research with a complimentary guest account.

We publish new research regularly. Subscribe to stay updated.

No spam.

Only the best in class fintech analysis.

Related Posts

- Samridhi Singh and Kshitija Kaur

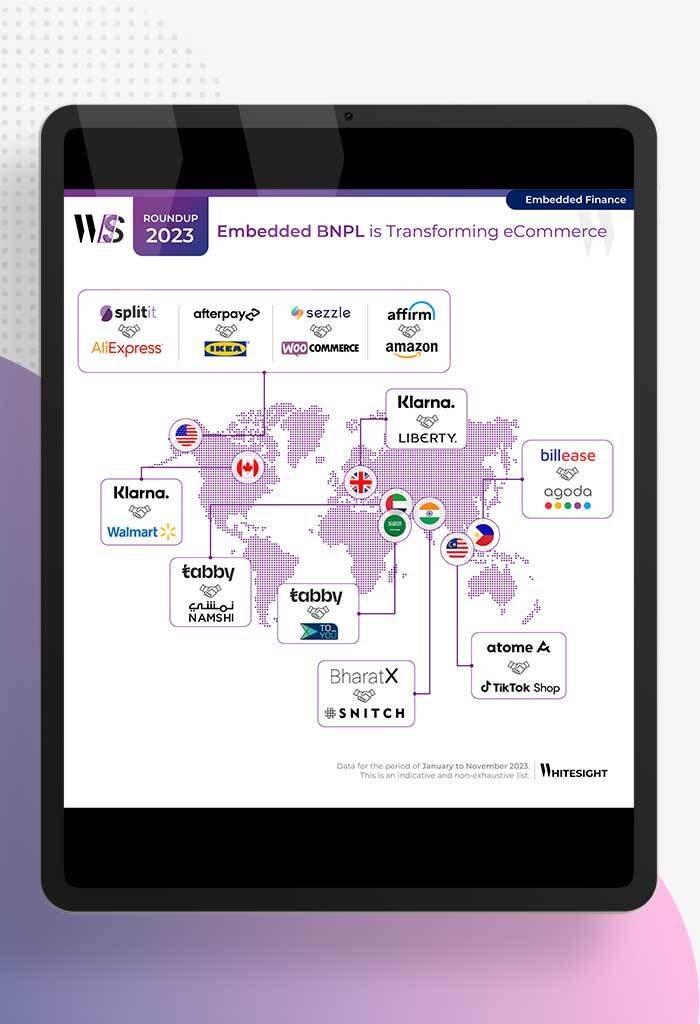

Swipe, Splurge, Savor: E-comm’s New Norm! What’s more fun than a Sunday shopping spree, right? Picture this: you on your...

- Risav Chakraborty and Kshitija Kaur

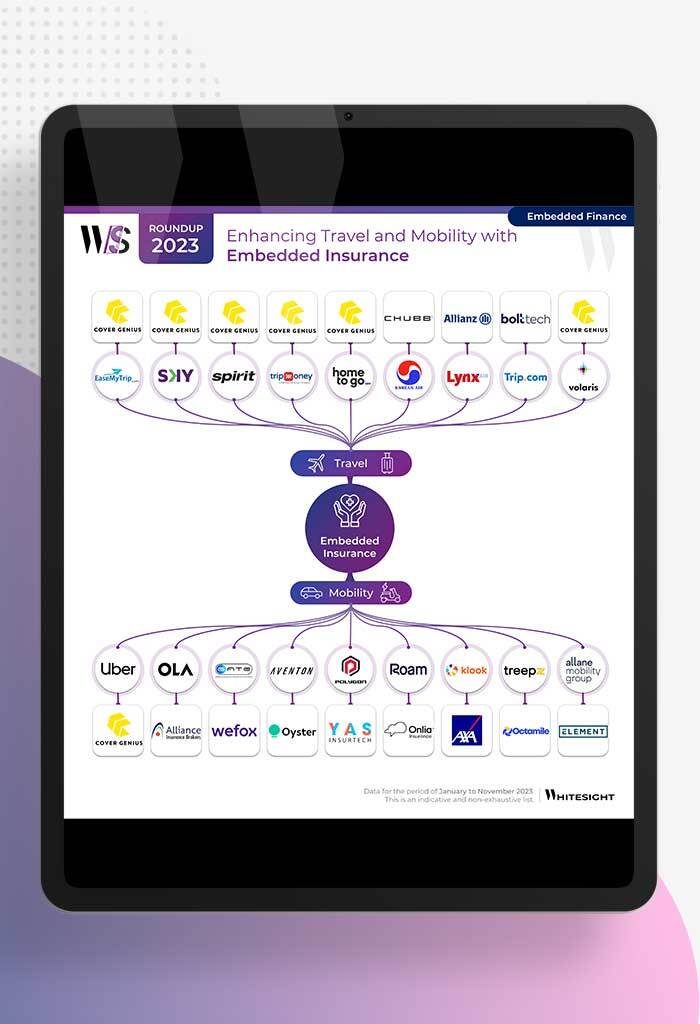

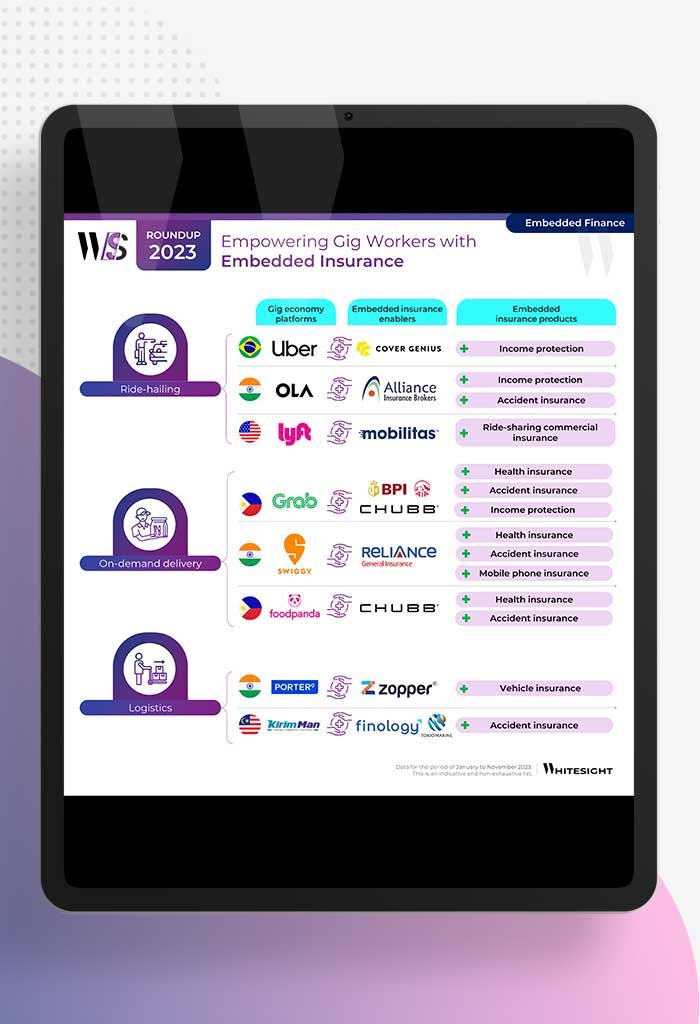

Drive Safe, Fly Secure: Embedded Insurance Escapade The travel and mobility sectors are roaring back to life now that the...

- Kshitija Kaur and Risav Chakraborty

Insurtechs: The New Guardians of the Gigaxy? Life in the gig lane is a rollercoaster, isn’t it? You’ve got the...

- Afshan Dadan and Sanjeev Kumar

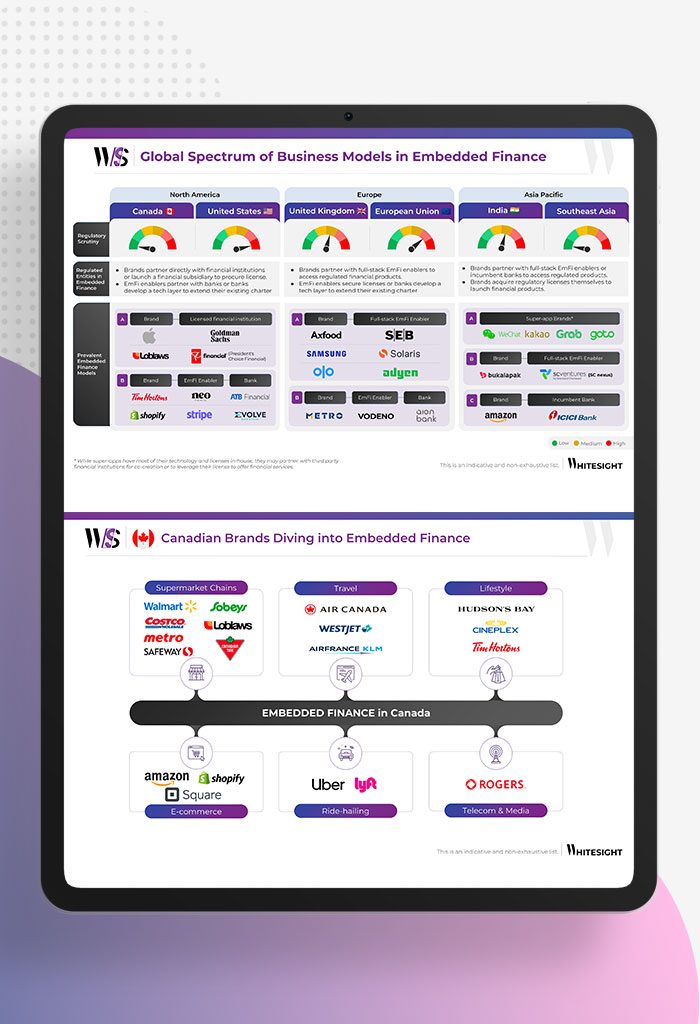

We’re going to go ahead and say it – 2023 is the year for embedded finance. This not-so-sneaky little trend...

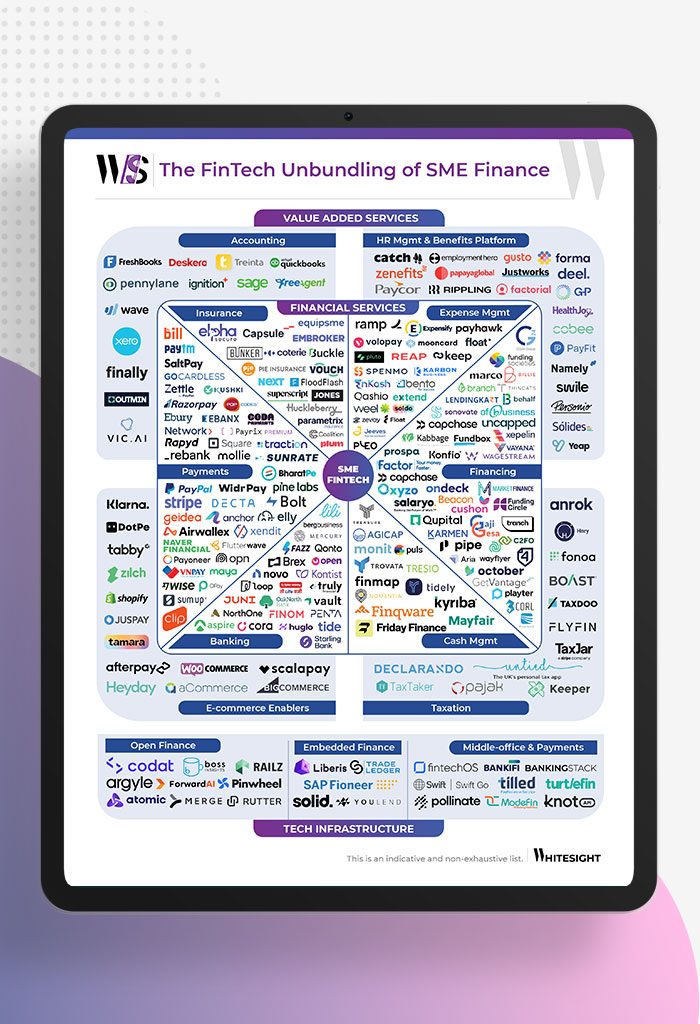

- Sanjeev Kumar and Afshan Dadan

In the ever-evolving world of finance, fintech has emerged as a game-changer, particularly for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). As...

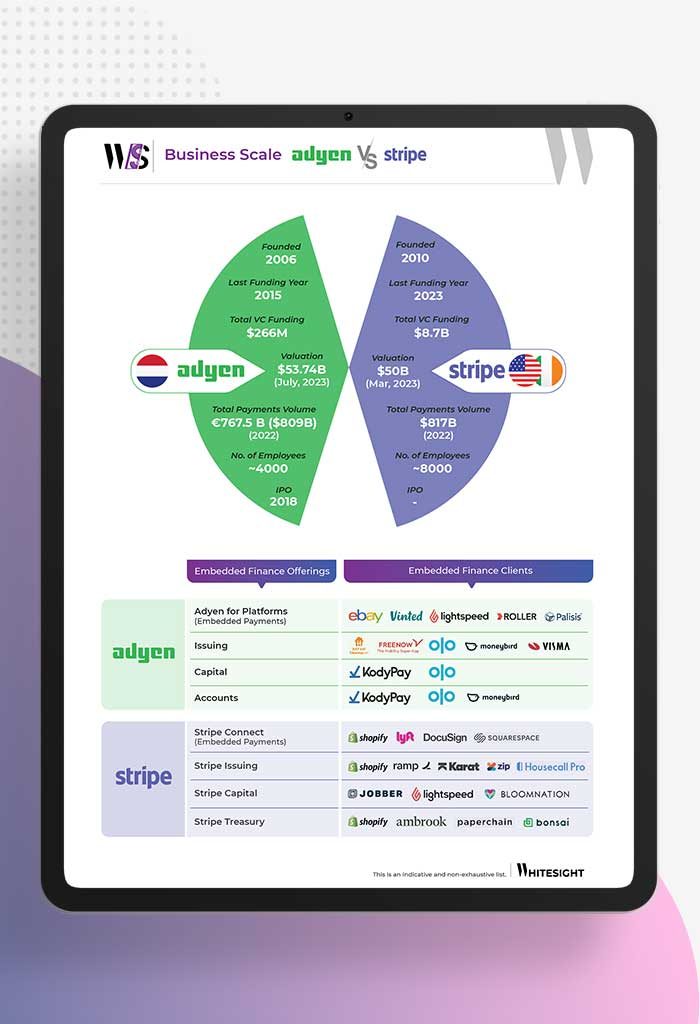

- Kshitija Kaur and Sanjeev Kumar

Payment processors had an incredible run during the pandemic, riding the wave of increased adoption of digital payments among merchants...