Behind the Synergy: Unearthing the Indian FinTech DNA

- Afshan Dadan

- 6 mins read

- Fintech Strategy, Insights

Table of Contents

India, as a market for financial services, is ripe with untapped potential. With a population of over 1.3 billion, 80% of which is banked, the financial literacy rates remain low at 27%. Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) that contribute 30% to the GDP of the country, represent a credit gap of USD 397 billion. These factors present opportunities for reform and more open financial services enabled by technology and digital infrastructure.The country’s fintech landscape has witnessed a flourishing symbiotic relationship between regulatory initiatives and infrastructure blocks, which have resulted in the perfect breeding ground for incumbents and insurgents to innovate upon. Over the last two decades, India’s zealous determination in bringing a paradigm shift in its vision for financial inclusion has led to the development of the India Stack, an initiative that aims to decode the country’s monetary problems through paperless, cashless, and presence-less API systems. The four distinct technology layers, covering areas of digital identity, digital records, consent, and a democratised payments interface, lay the holistic foundation for synchrony between infrastructure and norms. The hybrid open finance model which doesn’t mandate participation but definitely incentivises it, creates healthy market competition for collaboration between the most established to the […]

This post is only available to members.

Already a subscriber? Log in to Access

Unlock this blog

Gain exclusive access to this blog alone.

Radar Subscription

Select a membership plan that resonates with your

goals and aspirations.

Not Ready to Subscribe?

Experience a taste of our expert research with a complimentary guest account.

We publish new research regularly. Subscribe to stay updated.

No spam.

Only the best in class fintech analysis.

Related Posts

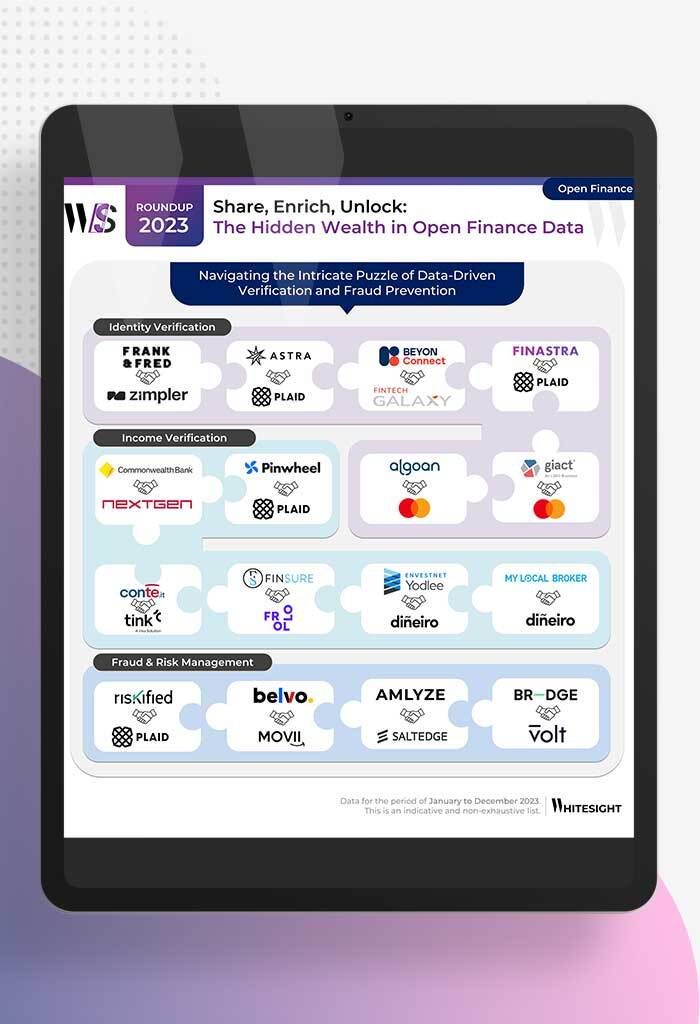

- Kshitija Kaur and Sanjeev Kumar

From Data Streams to Enriched Data Fountains Remember the early days of plumbing? Water flowed freely, but its quality was...

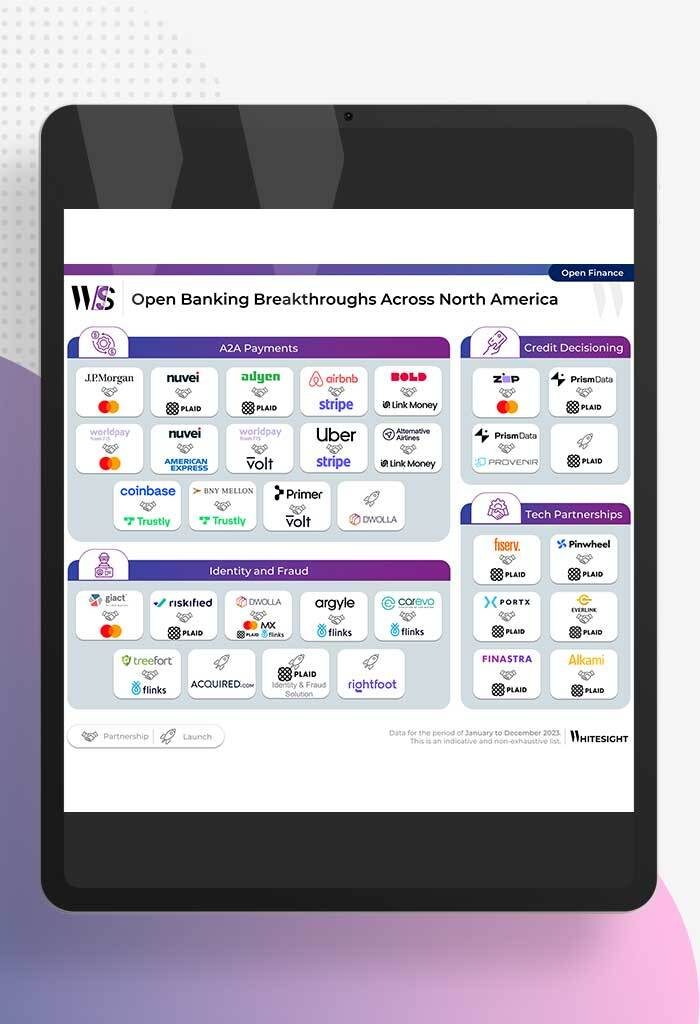

- Samridhi Singh and Sanjeev Kumar

North America’s Open Sesame: Use Cases Bloom Open banking has garnered significant attention in recent years, and at Whitesight, we’ve...

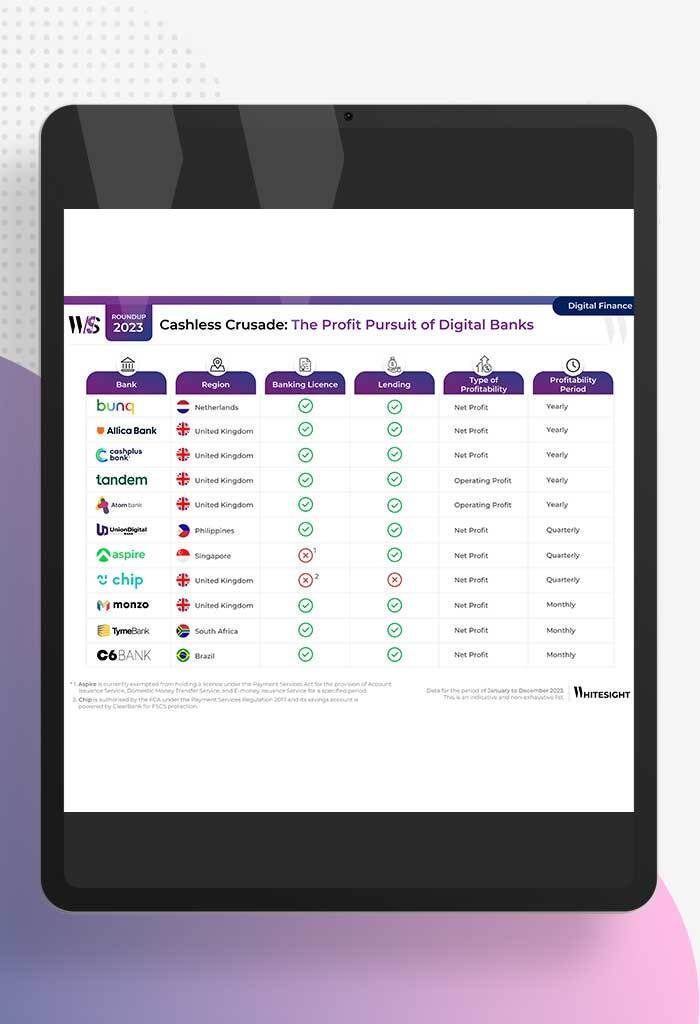

- Samridhi Singh and Sanjeev Kumar

Profitability Unlocked: Licences, Service, and Survival The rise of digital banks has sparked a paradigm shift in how we perceive...

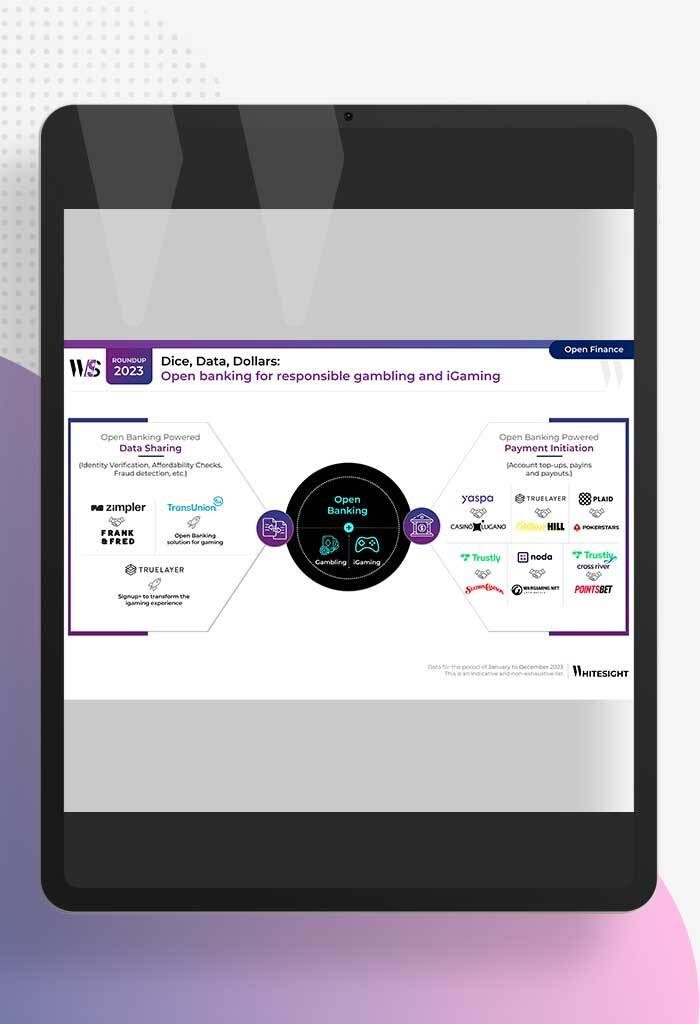

- Sanjeev Kumar and Risav Chakraborty

High stakes in the gambling sector The online gambling industry is booming, with a projected market size of $107.3B by...

- Sanjeev Kumar and Risav Chakraborty

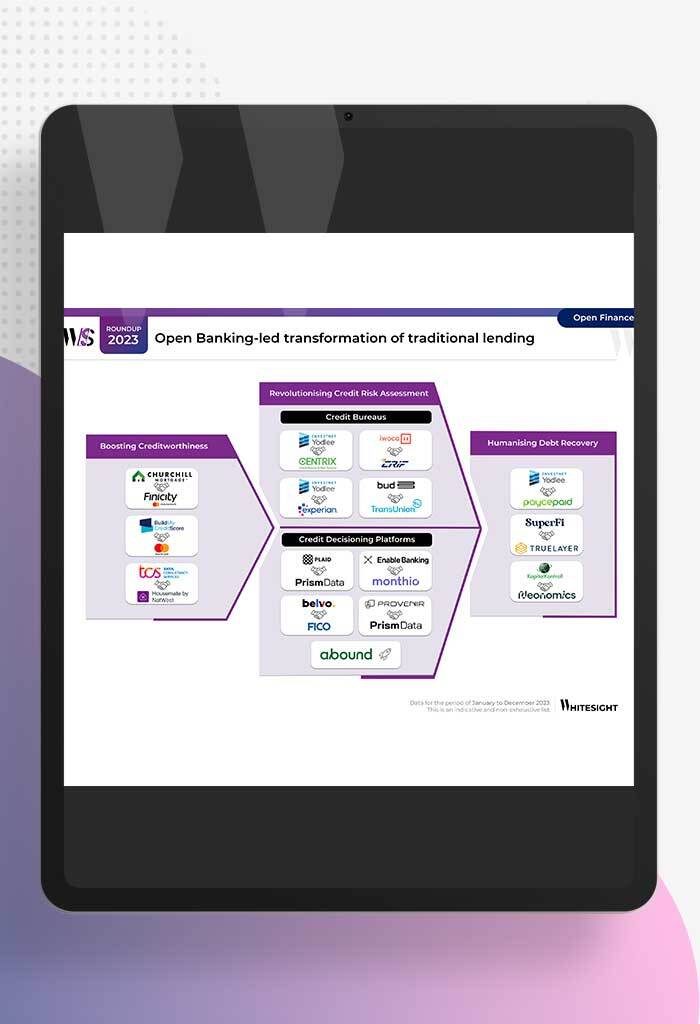

Open Banking-led Transformation of Traditional Lending In 2023, a wave of innovation swept through the lending industry, thanks to several...

- Sanjeev Kumar

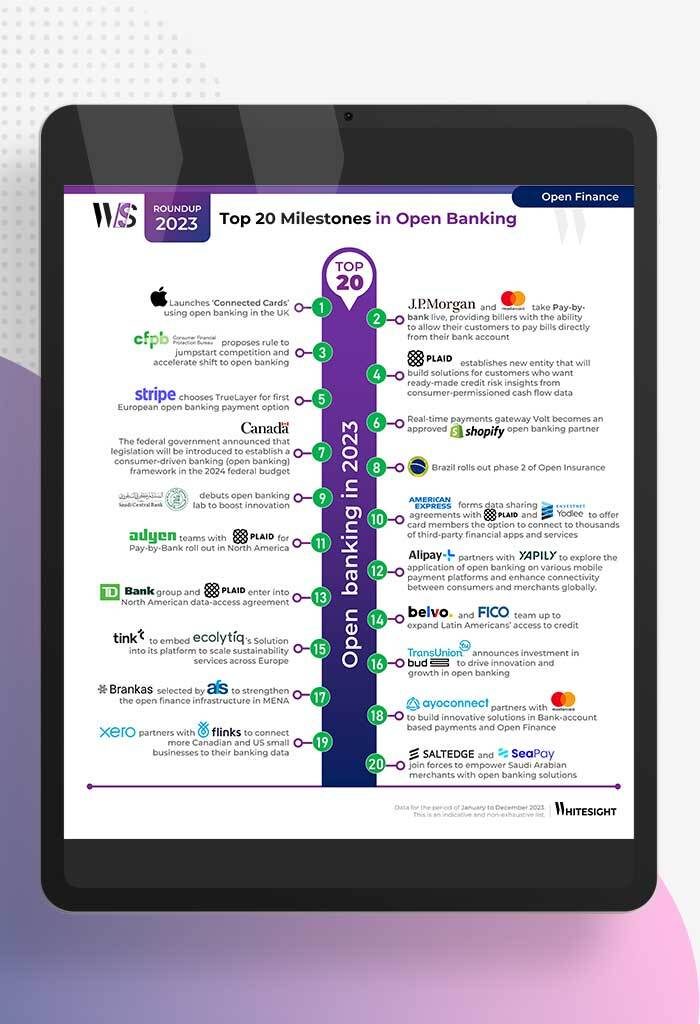

Unmasking Open Banking’s Game Changers in 2023 2023 has been a pivotal year in the world of open banking, marked...